OK, let’s talk poop.

OK, let’s talk poop.

As promised in my April 2 post, I plan to do a series of short posts about specific medical topics since I recently returned from “doctor’s school” in San Diego at the American College of Physicians meeting. Missed that post? Re-visit it at “Should you trust the latest medical advice?”

Today’s post will cover C. difficile infections, or CDI. This may be the ickiest post I’ve yet done!

First, a warning. What you about to read may make you go “Ewwww” and may make you wonder what kind of people actually talk about this stuff in polite company. I’ll tell you who talks about it . . . a bunch of doctors in a classroom on a sunny San Diego day. That’s who talks about it. Lucky for you, I’ll summarize here.

Yes, Clostridium is difficult

Imagine the uncontrollable need to evacuate your bowels 5, 10, 15 times a day. And when you do, it’s watery and you get really crampy. Sometimes you have a fever, sometimes there’s blood and mucous in your stool, sometimes the cramps are not just minor but are really uncomfortable, even painful. Sometimes you get dehydrated, your heart rate goes up, and your kidneys even start to shut down. Not a situation you want to be in.

This is not your 24-hour stomach bug. This is C. diff (the medical term is Clostridium difficile colitis). And the sobering part is that nearly half a million people will come down with CDI in a single year in the US.

Clostridium difficile is a bacteria that is present in the gut of some (but not all) people. It is contagious since it forms spores that get shed from the intestine of an infected person and those spores can live on inanimate surfaces for a loooooong time. We’re talking months here. So once you get it, there’s a decent chance it will come back again and again. And spread to others.

For the nerdy among you (like me, own the nerdiness!), the name of the bug is in the usual Genus species format:

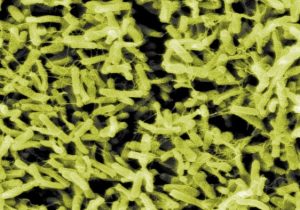

Clostridium = Greek (klōstēr) for spindle. Apparently the bug looks like spindles used in cloth weaving.

difficile = French spelling of the Latin difficilis meaning difficult. Duh. This is because in the early days this bacteria proved difficult to grow in the lab. Today we may as well concede that it should be named thus because it is so dag-blasted hard to eradicate!

Photo above is the bug. Photo at right are weaving spindles. I dunno. Sort of a stretch to compare the two, methinks. But since the bug was named in 1935, I guess they had to get creative with names. Now we just say “C diff” to sound cool.

Why talk about C diff now?

When I was in medical training in the late 1990s and early 2000s, C diff was only a disease of hospitals and really sick and vulnerable people. You simply did not hear about relatively healthy people living their usual lives coming down with C diff colitis. But it was a serious problem in hospitals. People had white counts (a measure of inflammation and infection) elevated into the stratosphere, they were hemodynamically unstable (you never want to be hemodynamically unstable, trust me), and often were in the intensive care units. Some people died of it.

Now we hear about it in the community. People walking around, healthy, coming down with nasty diarrhea. If you want the scholarly discussion of the whole issue, read this. For my somewhat less scholarly and cheeky discussion, read on.

So why the increase in C diff now? In a word: antibiotics.

People can get C diff without a previous exposure to antibiotics, but it is the dominant reason that today we see much more community-acquired infections (CDI is the acronym for Clostridium difficile infection). Here’s the play-by-play:

- Patient (could be you) gets a sinus infection. Or bronchitis. Or a skin infection. Or a urinary infection. Whatever. Nothing major. Time to go see doctor.

- In the clinic, the doctor prescribes an antibiotic for whatever ails Patient.

- Patient dutifully takes all the antibiotics. Whatever ailed them to begin with gets better.

- The antibiotic, not being too particular about what bacteria it kills, effectively eliminates the majority of the good bacteria in Patient’s intestines.

- What’s left is a hearty colony of C diff merrily replicating and basically setting up shop in Patient’s intestines. Yoo-hoo! We have the place all to our toxic selves!

- C diff produces a toxin which wreaks havoc all over the place.

- All hell breaks loose in there. Inflammation of the colon wall, destruction of the lining of the intestines, all lead to the nastiness Patient experiences.

- All the while, C diff is shedding spores into the stool which are basically the critter’s offspring. Spores get all over the place in the environment – on doorknobs, phones, countertops and they can live for months there.

- Unsuspecting people get the spores on their hands, touch their mouths, and the bug invades the new person.

- And so it goes again and again.

But why is CDI becoming more common?

The crafty among you have guessed the reason why? Too many antibiotics are prescribed in our world. Antibiotics are important for fighting infections and are quite literally life-saving and necessary in the right situation. But according to the Centers for Disease Control (a trustworthy source), as many as 1 in 3 antibiotic prescriptions written today are unnecessary. Click the link for more from the CDC. It is eye-opening.

Turns out we need those bacteria in our intestines!

What did I learn in San Diego about the latest in C diff?

The treatment of CDI is not all that new. If you get a CDI, your doctor will prescribe an additional antibiotic that is effective against this specific bug. Usually this is metronidazole or vancomycin. Sometimes fidaxomicin. It works most of the time. But not always. Recurrent CDI is common (1 in 4 people will get another bout after finishing the antibiotics).

Here’s the part I learned recently: there is NO POINT in re-testing a patient’s stool after the first bout of CDI. Many doctors are still doing this. The test for C diff is a stool test so if your symptoms come back, many doctors re-test your stool. But since the toxin can persist for a long time, a repeat stool test is not needed. What are you going to do if the repeat test still shows toxin? Probably re-treat the patient. What are you going to do if you don’t get a repeat stool test? Probably re-treat the patient anyway based on their clinical symptoms.

When a test does not change what a doctor is going to do there is no point in doing that test.

Fecal transplant is a fancy way to describe an unpleasant situation

OK, I’ll close with the biggest ewww-inducing part of this whole subject.

Here goes. Brace yourselves.

If all the antibiotics don’t work and Patient continues to get bouts of CDI over and over, there is another approach which is to put the stool of one person into the intestine of the one with CDI. You read that right. One person donates stool to another. The idea is that by restoring healthy bacteria into the intestine, the C diff will no longer have free reign over your intestines. It actually works and yes, it is actually done. I’ll spare you the details. I kid you not, there is actually a support group for this, called the Fecal Transplant Foundation, if you want to learn more. Talk about natural medicine! Although I do have to say the couple on the front page of that website look altogether too composed and cheery given the procedure they are contemplating.

The take home points:

- Be wary of taking antibiotics for minor conditions.

- If you get CDI, get it treated.

- If you get diarrhea again, it is probably a recurrence of your previous infection and will likely need re-treatment.

- Repeat stool testing is unnecessary.

- Wash your hands frequently if you or a close contact has CDI.

So that’s it for C diff. I plan to do posts about what I learned at the American College of Physicians meeting over the coming months. Leave me a comment below if there is a specific condition that interests you.

-David