Hi, everybody! For about 2 months I’ve been yammering both in this blog and on the radio broadcast about the current Healthy Matters online book club selection, and it’s time to get to it! As they say in billiards .. “Quit talking and start chalking . . . “

Hi, everybody! For about 2 months I’ve been yammering both in this blog and on the radio broadcast about the current Healthy Matters online book club selection, and it’s time to get to it! As they say in billiards .. “Quit talking and start chalking . . . “

I don’t know about you, but I’ve been reading How Doctors Think by Jerome Groopman. For regular readers of MyHealthyMatters, hopefully you’ve had a chance to check it out. But it’s OK if you didn’t read the book. I’ll bet you’ll have something to add to the conversation even if you didn’t get to read it!

To get you thinking, I’m going to talk about the book in the following format:

- My summary and reflections about an aspect of the book, broken into 3 topic sections

- A few questions for you to consider in response to my reflections. Hopefully you’ll leave a comment at the bottom with your own thoughts.

I’d rather this be a two-way conversation – an online book discussion – rather than just me talking. (I talk enough). I’m most interested in your thoughts so please join the conversation even if you didn’t get a chance to read the book. (Just like in-person book clubs where half the people didn’t actually read the book! You know who you are.)

My observations on How Doctors Think

First topic: Who is the book for?

Me. Thinking.

The cover of the book says “Must reading for every physician who cares for patients and every patient who wishes to get the best care.” Fair enough. But my first impression about this book is that is it meant for doctors to read. After all, through a series of stories and case examples, Dr. Groopman outlines the various ways a doctor can make a mistake in diagnosing a patient’s illness. So I guess we doctors should take heed. I admit I rather admire him for laying it all out there. In example after example, he educates us about various cognitive errors – ways in which a well-intentioned clinician can be wrong.

To be honest, from my perspective as a physician, the stories he told about the various ways doctors mess up could have come from my everyday life. I confess I have made these exact same diagnostic mistakes. Whenever the book talked about a doctor’s error in diagnosis, I thought . . . There but for the grace of God go I . . . Actually, I think my colleagues in medicine think this quite often.

But was the book helpful to people who aren’t doctors? That’s what I hope some of you will answer. Dr. Groopman’s tales of mistake-prone doctors felt a bit repetitive to me. Did it feel that way to you as well? For those of you who did not get to read the book . . . the book is a series of essays that use stories of doctors making diagnostic errors, followed by a rather professorial look at the type of “cognitive errors” that they make.

Questions for you

- If you read How Doctors Think, who do you think the intended audience was? Doctors? Or patients?

- As a patient, does it help you to know about the medical decision-making process, as this book describes it? Or does it leave you somewhat disillusioned that your doctor does not, in fact, have all the answers?

- Does it surprise you that doctors make as many diagnostic errors as this book describes?

Leave a comment on these questions on the bottom of this post!

Second topic: Cognitive errors

The book gets into some detail about cognitive errors. When the author does this, I can’t help recalling some of my medical training, where they actually did cover this type of thing – in about one hour. Not exactly an in-depth lesson in medical decision-making. I found his explanations of cognitive errors a bit too academic, but hey – the author is a big-time professor at one of the world’s best medical schools (a little school called Harvard) so I guess he can be forgiven for having it come across as “academic.”

I’m going to take a shot at some of the errors in medical thinking that doctors are prone to doing. When you read these, try to think if you have ever encountered a situation where your doctor did a similar thing. I’ll give the page number from How Doctors Think where he talks about each error.

Is it alcohol or gallstones? Availability errors (pg 64).

An availability error is when your doctor diagnoses you with something simply due to the ready availability of similar cases in his or her experience.

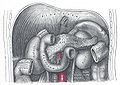

Photo:Henry Vandyke Carter – Henry Gray (1918) Anatomy of the Human Body

Examples from my own experience come to mind. For instance, where I practice medicine, we see a large number of people with the illness of chemical addiction. (Note that addiction is an illness, not a character flaw or personal weakness. Important distinction.) When a person with addiction, let’s say to alcohol, comes in with severe belly pain we often jump right to the diagnosis: alcoholic pancreatitis. And in fact at my hospital that is usually the correct diagnosis. But it is also a fact that gallstones can lead to identical symptoms: gallstone pancreatitis. So the high prevalence of alcohol dependence in my patients may cause me to assume that the next patient also has alcohol pancreatitis. (In the diagram at left, that’s the pancreas smack dab in the middle, surrounded by liver and intestines.)

Pancreatitis due to alcohol is treated very differently than pancreatitis due to gallstones (medicines vs surgery). But what if that patient, despite alcohol use, has gallstones this time? I would miss the diagnosis and do the wrong treatment if I don’t resist the availability bias.

Question for you

- Do you think a doctor has ever assumed something about your diagnosis just because something is common in his/her experience?

Leave a comment on these questions on the bottom of this post!

Cable news and Emergency Departments: Anchoring errors and confirmation bias (pg 65).

Confirmation bias exists all over our world, not just medicine. You are succumbing to this error in judgment whenever you selectively see information that serves to confirm what you already believe. To use the author’s terms, you “cherry pick” what you choose to pay attention to.

An immediate example comes to my mind when thinking about cable news networks. How many of us watch the news shows, or read the newspapers, or frequent the websites for news that basically agrees with what we already believe. Let’s be honest . . . Fox News is not news in any sound journalistic sense. Nor is MSNBC. One of them spews out a brand of opinion and perspective that resonates with more conservative viewers while the other does the same for more liberal viewers. Neither one of them challenges their viewers to consider a different perspective. The effect is to reinforce what we already believe, not expand our knowledge.

Is it heart failure . . . or something else?

The same happens in medicine. An example again from my own experience . . . as a doctor who mostly cares for patients in the hospital, I admit people who were first evaluated in the emergency department. I happen to work at a place where the Emergency Department is top-notch. I really mean it, they are the best in the region at caring for acutely ill people in the emergency setting. But consider this scenario . . . .

A 75 year man comes to the Emergency Department. He has a history of heart failure that requires frequent hospitalizations. As a hospital doctor, I personally have met him many times for this exact reason. He gets short of breath, goes to the emergency department, gets diagnosed with heart failure, put on diuretics (medications to make a person urinate out excess fluid) and admitted to my service to further manage his heart failure. I carry on with the treatment of heart failure over the coming days but he doesn’t get much better.

What’s going on? I’m doing everything correctly. He has a well-known heart failure problem, he is here for another episode of the exact same thing and I’m giving him all the right medications.

But wait . . . heart failure isn’t really known for causing a fever, and I notice that when he first came in he had a high temperature. Funny I missed that bit of information when he first arrived. So did the doctors in the Emergency Department.

Photo: Walter Serra, Giuseppe De Iaco, Claudio Reverberi and Tiziano Gherli

And after talking with him a bit, he tells me that his right leg has been swollen much, much more than the left leg over the past week, and it happened really suddenly. That’s funny, in heart failure, usually both legs are swollen and it is strange to have one leg suddenly get big and swollen. Seems I missed that important bit of information as well.

So this patient had a blood clot in his leg that migrated to his lungs. That is called a pulmonary embolism and for all the world it looked like heart failure when he showed up. Those are bilateral (both sides) pulmonary emboli in the CT scan picture above. Light color = flowing blood in pulmonary arteries (good). Dark spots = clot (bad). See the arrows?

In this case we committed an error of confirmation bias. We believed he had heart failure the minute he showed up in the Emergency Department. The ER doctors thought so and I thought so after he arrived in the hospital room. Heck, even the patient thought so. After all, it felt like the same problem he usually has and that we all believed he had this time as well.

And we chose to see only the information that confirmed our initial beliefs. Just like the cable news shows. But just like the cable news viewers, we would have done well to consider a different viewpoint. Consider the possibility that something other than our preconceived notions might be true. We didn’t pay adequate attention to the clues that maybe his shortness of breath was something else. That fever, that swollen leg – warning signs of a blood clot.

Questions for you

- Has a doctor even assumed something about your medical problem based on pre-conceived notions of what he/she already believed you had?

- How can you as a patient be a full participant in the medical decision process so that your doctor doesn’t miss important clues?

Leave a comment on these questions on the bottom of this post!

Topic 3: The perfect is the enemy of the good

To close out this discussion on How Doctors Think, please consider the phrase “The perfect is the enemy of the good”

I used to have a position in my hospital as one of the medical education leaders for our internal medicine residency program. Our job was to shepherd ~60 new doctors through their 3-years of residency training. Hopefully, by the end of the 3 years, we could graduate them into independent practice in the community. It’s a big responsibility.

The program director, who is a good friend of mine and now works at a big Medical School, used to remind us to be wary of letting “the perfect be the enemy of the good.” She’s really smart and I still remember her saying this.

Dr. Groopman uses the same phase on page 173 of this book. But what does it mean?

Basically it means that just because one course of action, or one outcome, or one treatment, is not perfect, that does not mean it is not still pretty good. And sometimes, good is all we can manage, and to be honest, that is OK.

Here are three examples of what I mean.

Pain control. We often ask patients in the hospital to rate their pain on a scale of 0-10, with 0 being no pain at all and 10 being the worst pain imaginable. Well, perfect pain control would be a “0 of 10” – but that is often not possible, at least, not without intolerable side effects (I can make you pain-free but you’ll be unconscious from all the medications). So we shoot for pain control that is tolerable. Maybe a “4 of 10” is the best we can do. Not perfect. But good. And a whole lot better than “10 of 10” pain.

Vaccinations. This is a big one with lots of emotional baggage. I bet I hear every single year many times something along the lines of . . “vaccines are not 100% effective” or “I still got (insert disease here) even though I got vaccinated” or some such reasoning used as a rationale for not getting vaccinated (or worse yet, not getting your kids vaccinated).

Courtesy of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History

Of course vaccines are not perfect! We still await the vaccine that is perfect. But getting vaccines reduces the chances of getting some pretty awful diseases, reduces the severity of symptoms if you still do get the disease, and protects the entire society of people by promoting “herd immunity.” All really good reasons to get vaccines. Just not perfect.

Medical education

My last example of the perfect as the enemy of the good goes back to my friend the medical educator. It involves a topic that makes us medical teachers squirm. Believe me, residency program directors constantly worry about the competence and skill of their trainees. Fortunately, the vast majority of resident physicians are highly skilled doctors!

The conversation goes something like this:

“What do you think of Doctor Z? You know, the one in the last several months of his medical training? Do you think he’s ready to practice”

Somewhere in this discussion someone usually asks, “Yes, he is a great doctor in almost every way . . smart, clinically good, kind . . . but I wouldn’t send my family member to him . . something about his style bugs me.”

Or something like that.

But finding a doctor that I would send my family member to is basically saying I am looking for the perfect doctor. It’s a pretty high bar. So it is not the right question to ask, because believe you me, the doctor who is good enough for my mother does not exist.

But we don’t need perfect in our doctors. We need good. That not-quite-perfect doctor from the previous discussion may have just exactly the style for many patients. He is a really good doctor. He is just not perfect.

Questions for you

- Have you found yourself in the “perfect vs good” situation? Were you a patient where you hoped for a better outcome than the doctor was able to promise?

- It takes a lot of honesty for a doctor to acknowledge that the best he or she can hope for is a pretty good result. Lots of doctors struggle with admitting that they are not perfect. What is your reaction to that?

Leave a comment on these questions on the bottom of this post!

So I hope you have found something to think about, either having read How Doctors Think by Jerome Groopman, or by slogging your way through my “stream-of-consciousness” ramblings in this post. And most importantly, I hope you will join the conversation by leaving a comment in the section below. Perhaps by respectfully responding to the comments of others. Maybe respond to something I have written. Or maybe you have some thoughts of your own about your experiences with your doctor. Share them here!

Next book: Suggestions wanted!

So far we have looked at 2 books in the Healthy Matters book club (When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi & How Doctors Think by Jerome Groopman). I’m looking for suggestions for the next book to read and discuss – probably will do a post this fall (September/October) on the next book.

Maybe it’s time for a work of fiction? Or some other great non-fiction that you know? Just so it has some medical slant of some kind, I’ll consider it, buy it, and get the conversation going. Leave a comment below with your suggestions.

David