My family just returned from a pilgrimage of sorts. Having returned from a journey to witness one of nature’s miracles – and picking up a bit of a health problem myself – I’m feeling all butterfly-ish.

My family just returned from a pilgrimage of sorts. Having returned from a journey to witness one of nature’s miracles – and picking up a bit of a health problem myself – I’m feeling all butterfly-ish.

Please read on for my story and some thoughts about health, both the human, the insect, and the planetary kind.

(Except where noted, all photos are © David Hilden. Amazing what you can do with a camera phone)

The amazing flight of the monarch butterfly

My wife, Julie, and I have been smitten by the story of the monarch butterfly for some time now. It is a story of an insect – the familiar monarch butterfly – and the incredible journey it takes during its annual migration from all over North America to its wintering habitat in the mountains of central Mexico.

I have been intrigued by animal migrations in other ways as well. Julie and I have witnessed gray whales as they migrate many thousands of miles from north to south in the Pacific Ocean. Another time, I drove 8 hours to a remote camouflaged stand along the banks of the Platte River in Nebraska to watch in silence as thousands of sandhill cranes landed in the river that is a “mile wide and an inch deep.”

Now the monarch butterflies. My friends, the word incredible is apt here – it truly is a natural wonder that is difficult to believe. The story goes something like this:

- Butterfly #1 leaves her winter habitat in the mountains of Mexico in the springtime. She makes it to Texas where she lays her eggs and dies.

- Butterfly #2, born in Texas, migrates northward to Iowa, lays her eggs, and dies.

- Butterfly #3, born in Iowa, flies further north to my backyard in Minneapolis, lays her eggs, and dies. It is now the fall.

- Butterfly #4, the great-granddaughter of Butterfly #1, is born in Minneapolis and flies all the way back to the same mountaintop in Mexico where her great-grandma lived.

Think about that. Minnesota is a long way from Mexico. Especially if you are a bug. Butterfly #4 doesn’t possess GPS and is not too good at asking for directions. And weirdest of all, Butterfly #4 has never been to Mexico. Neither has her mother. Or her grandmother. So it’s not like she has been there before and has some memory of her youth in Mexico. That little insect has literally never been outside of Minneapolis, yet finds her way all the way to Mexico. And that story is repeated with millions – maybe billions – of other butterflies across the continent.

In-cred-i-ble.

This happens to all the butterflies of North America east of the Rockies. I guess the California monarchs go someplace else. But the monarchs from Minnesota, Ontario, New York, Florida – they all end up on this same patch of Mexican mountainside.

Planes, trains, and automobiles . . . and horses

So my family took a plane to Mexico City, then a taxi to the bus terminal, then a bus into rural Mexico, then another taxi to even more rural Mexico, then a horse up the mountain, then walked higher up the mountain.

What we found up there at 10,000 feet was breath-taking.

Here’s the sky that greeted us:

And the ground below us:

We sat there for two hours, largely in silence, while the monarchs sought out the sunny warmth. While sitting still, it was only a matter of a few seconds before butterflies would land right on us, sometimes many at the same time. One crawled on my ear and I could barely resist the urge to scratch it!

We sat there for two hours, largely in silence, while the monarchs sought out the sunny warmth. While sitting still, it was only a matter of a few seconds before butterflies would land right on us, sometimes many at the same time. One crawled on my ear and I could barely resist the urge to scratch it!

Our guide, a young Mexican woman who had grown up on this mountainside, helped us identify the male and female butterflies (if you are interested, the male has two dots – of uncertain significance – on the lower part of his wings. See the difference in these pictures?

I was able to get close enough for my own scientific study: This monarch is female (no black spots):

While this one is a male (note the black spots):

Why care about monarchs?

I am fascinated by these creatures, and perhaps you are as well. But for those of you living in northern places, like me, ask yourself: are you seeing as many monarch butterflies in your yard as you used to?

I don’t think I am seeing as many. That worries me.

It worries me because as natural populations go, so goes our human population. When monarchs populations are not healthy, I can’t help thinking that our human population isn’t too healthy either.

In Mexico, they measure the monarch population by counting the number of trees covered in orange. This year, at the reserve I visited, they said they were something like 50 trees covered in monarchs. Just 50 trees for the entire monarch population of North America east of the Rocky Mountains. That doesn’t seem like too many.

![2007 Derek Ramsey (http://www.gnu.org/licenses/old-licenses/fdl-1.2.html)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://healthymatters.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Common_Milkweed_Asclepias_syriaca_Flower_Head_3008px-300x199.jpg)

2007 Derek Ramsey (http://www.gnu.org/licenses/old-licenses/fdl-1.2.html)], via Wikimedia Commons

The threat to the monarchs is really not too difficult to fathom. It all comes down to milkweed. This humble plant – a weed, really – is the sole place monarchs can lay their eggs. No milkweed = no monarchs.

Milkweed is found all over. I planted a dozen plants in my yard. You should too. But perhaps even more importantly, milkweed can often be found at the edges of farms and by the sides of roads, and this milkweed is susceptible to our endless need to spray chemicals. Whether it be your backyard garden, the edge of a big cornfield in Iowa, or along Interstate 35 in Texas, we need to allow the milkweed to grow and flourish.

We need to stop using so many chemicals on our planet. The butterflies are telling us this and I firmly believe we need to listen.

That is the message of the monarch.

From butterflies to bacteria

The second part of my Mexican story is about intestinal bacteria. Sexy topic, I know.

After leaving the sanctuary of the Mariposa Monarcha, my family headed to a favorite hideaway spot, the seaside town of Sayulita in the Pacific coast state of Nayarit, Mexico. It’s simply a lovely town. Has a surfer vibe, with the waves crashing on the beach amid local surfer dudes. It’s a small town, with perhaps a few thousand people in what must have once been a fishing village. Now it is a mix of local Mexican people and tourists like us. Cute little sidewalk restaurants line the streets and art galleries intersect with “mini-supers” selling jalapeño peppers for 3 pesos (about a dime) each. We love it.

After leaving the sanctuary of the Mariposa Monarcha, my family headed to a favorite hideaway spot, the seaside town of Sayulita in the Pacific coast state of Nayarit, Mexico. It’s simply a lovely town. Has a surfer vibe, with the waves crashing on the beach amid local surfer dudes. It’s a small town, with perhaps a few thousand people in what must have once been a fishing village. Now it is a mix of local Mexican people and tourists like us. Cute little sidewalk restaurants line the streets and art galleries intersect with “mini-supers” selling jalapeño peppers for 3 pesos (about a dime) each. We love it.

What I especially love about this part of Mexico – and well, really, every part of Mexico that I have visited from the megalopolis of Mexico City to the tiny town of 300 people and 100 horses in the mountains – is that people are so kind. I can’t recall a single encounter with a Mexican person on our recent trip that was anything but smiles and friendly faces and warmth all around. It struck me how much in common we have with other people from around the world.

So I’m a bit of an adventurous traveler, as is my family, and we ate lots of yummy food. Sometimes perhaps we were a bit too adventurous. Eating fresh grilled mahi-mahi from a street vendor is perhaps OK (it was cooked!) but maybe the raw pineapple chopped up on a roadside cutting board . . . well maybe not so smart.

In any case, I came down with a case of the intestinal whatevers in a bad way. My whole belly felt like it was being twisted and stretched. Then the fever hit. Then the many trips to the bathroom for . . . well, you know what for.

At least it was just me and the family was OK. Until they weren’t. First our son got sick. Then several hours later our daughter fell ill. My wife, apparently the one with the strongest intestinal defenses, never became really sick but she was always on the edge of a bloated tummy.

So I got to thinking about why we all got sick. Here we were, having done the butterfly thing, now relaxing in a seeming paradise of palm trees, ocean air, delectable food, and simply lovely local people.

It all comes down to water.

We got sick for a pretty simple reason. Water in this part of Mexico is not safe.

So we buy millions of plastic bottles for our water. And we avoid local foods. And we brush our teeth with apprehension lest we get sick. For the most part, we as affluent tourists do OK. With a bit of luck and just a little planning, we can be safe.

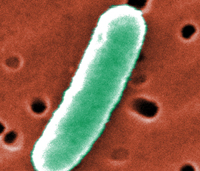

2008

Janice Haney Carr

But without adequate sanitation and clean water, those little ETEC (enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli – probably what I had) and their microorganism friends get into the water, and onto the cutting board, and onto my food, and into my belly. The little town of Sayulita simply doesn’t have the resources to ensure safe water and sanitation for its people, much less the tourists. The little river flowing into the Pacific through Sayulita was basically an open-air sewage ditch. The sanitation system just cannot handle the by-products of human habitation.

This is true for most of the world. I did a bit of research. According to the United Nations, nearly 800 million people do not have access to clean water, and an astounding 2.5 billion people do not have adequate sanitation.

With a sigh I admit this troubles me. Maybe you as well.

I was thinking as I was making my umpteenth trip to the bathroom in Mexico that this ought to be a problem we can solve. Sewage technology must be something achievable. Safe water is not un-attainable. But these are the things that are huge determinants of health. For those of you not in the public health field, determinants of health is an important concept and something which I think – even as a medical doctor – is more important than anything I do in the clinic.

We simply wouldn’t need as many doctors if we had safe water and adequate sanitation for the world’s people. I am not an environmental scientist but I have enormous respect for the men and women who scientifically study the health of our planet and for those people who are actively working to promote a healthy planet for all people. Not just the affluent people.

So that’s my story. Butterflies and bacteria.

More resources

If you want to learn more, I recommend these sites:

The Monarch Lab from the University of Minnesota (my alma mater) is a loaded with monarch information, links, and even a store to buy monarch goodies. I’m really excited about this site!

For information about global water issues, check out the United Nations Water Cooperation site.

Thanks for checking in with me. I hope this got you thinking about more than butterflies and my intestinal problems.

Healthy butterflies. Healthy water. Healthy planet.

-David

Please subscribe by e-mail if you like what you see here. And don’t forget to follow me on Twitter @DrDavidHilden.